Finn på siden

NATO in the Arctic: Three Suggestions on NATO and Security in the Arctic

As the past few days have shown, whether Russia is a threat to the liberal international order is no longer a question. This note presents the case that NATO now have the chance take a decisive stance against Russian attempts at coercive diplomacy and outright military threat. NATO could enhance their Arctic security by many degrees by establishing a credible presence and deterrence in the Arctic.

Publisert: 4. mars 2022

Av Kristian Brekke, bachelorstudent i internasjonal politikk og militær historie ved Aberystwyth University

Will NATO forget the Arctic again?

The first decade of the 21st century was a period of optimism regarding security cooperation with Russia in the Arctic. This changed from 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea. In late February 2022 Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Optimism has turned to pessimism. Five NATO-members are Arctic states: the USA, Canada, Norway, Denmark and Iceland. Two other Arctic states – Sweden and Finland – have close ties to NATO.

Long before the Russian invasion of 2022 Canada’s defence policy saw Russia’s aggression against Ukraine as one of several indications of renewed major power competition, which calls for strengthened deterrence, including in the Arctic (Canadian Armed Forces, 2017: 50). Sweden, Norway and Finland all developed new strategies for the Arctic in 2021, with Denmark’s new Arctic strategy set to be published in 2022. In the four Nordic states the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, and general political and military pressure against neighbours, caused a fundamental shift in the perception of Russia from trustworthy partner to a security challenge (Working group of public officials responsible for Arctic issues, 2021: 18; Regeringskansliet, 2020: 19; Det Kongelige Utenriksdepartement, 2020: 10). With the invasion of 2022 these perspectives seem more relevant and more urgent.

In NATO, the Arctic has mostly been an afterthought because it has been seen as a region with low potential for conflict and the alliance’s focus has been on the Baltic and Black Sea regions (Coffey and Kochis 2021). At the NATO summit in Brussels in June 2021 the member states agreed to develop a new strategic concept to be finished before the summit to be held in Madrid 2022. The Arctic is not high on the agenda for the NATO 2030 initiative. However, the Arctic will be a particularly important region for NATO-Russian relations for several reasons. Firstly, Russia’s economy is becoming increasingly brittle and about 45% of their economy now relies on oil and gas export to Europe according to US President Joe Biden (Biden, 2022: at approx. 31 min.).

The Arctic has “approximately 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil resources and about 30% of its undiscovered natural gas resources” (World Economic Forum). As the Arctic thaws as a result of global warming and the region opens up to the possibility of exploitation of oil and gas resources, Russia’s neighbours should prepare for contention over control of these resources. This is recognised by Sweden’s new Arctic strategy. In the chapter on ‘säkerhetspolitiska trender’ (security trends) they recognise the natural resources in the Arctic as the most important catalyst for conflict (Regeringskansliet, 2020: 23). Secondly, climate change also means that sea-routes between the Atlantic and the Pacific along the Arctic coast of Eurasia are opening up. These sea-routes can potentially entail a reduction in travelling time between some of the world’s biggest markets by several dozen percent (World Economic Forum, 2020). NATO must be prepared for situations where a belligerent Russia attempts to violate international laws pertaining to freedom of navigation through the North Sea Route and the Northeast Passage; Moscow is already claiming several of them as sovereign waters (Skydsgaard & Pamuk, 2021). As the past few days have shown, whether Russia is a threat to the liberal international order is no longer a question. Thirdly, a coherent Arctic strategy will be imperative to defend the Arctic NATO states as well as the sovereignty of Finland and Sweden. Both countries experience an increasingly coercive and threatening neighbour in the east (Braw, 2022; Mackinnon, 2022).

The collapse of NATO-Russian cooperation in the Arctic

There is a scholarly debate on whether the Arctic is or is not the ‘new South China Sea’ (Buchanan & Strating, 2020). This debate is mainly rooted in the differing viewpoints of the neoliberal institutionalist and neorealist frameworks (Keil, 2013: 164f.). On one hand, the institutionalist framework claims that strong international cooperation and institutions can remove, or at least reduce, the potential for conflict in the Arctic. On the other hand, the neorealist approach claims that institutions will prove insufficient to “play a decisive role for the achievement of stability” (Keil, 2013: 165). I mention this because the latter of these frameworks seemed to be proven right in 2014 when the annexation of Crimea led to the deterioration of military cooperation and inter-regional diplomacy between the Kremlin and the rest of the Arctic Council. This collapse of Russo-NATO relations directly influenced the Russian decision to withdraw from the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable and the suspension of the Arctic Chiefs of Defence Conference (Depledge, 2020: 84).

This is in stark contrast to the close cooperation that characterised the Arctic Council before 2014. Prior to the annexation of Crimea and now the institutionalist assumptions that security could be reached through Arctic institutions and cooperation were dominant. This approach also included the belief that NATO presence in the region would erode cooperation and trust, which led Canada to vetoing all calls for enhanced Arctic security within NATO (Depledge, 2020: 81). The European Arctic countries were also apprehensive of NATO involvement in the Arctic and thus “showed a steadfast reluctance to provoke the Russian military and endanger close commercial ties” (Zeman, 2021). However, after the annexation of Crimea this institutionalist approach has been upended and NATO Arctic states along with Sweden and Finland “have

uniformly shifted to enthusiastically endorsing United States–led security cooperation and partnership in the Arctic in their strategic documents” (Zeman, 2021).

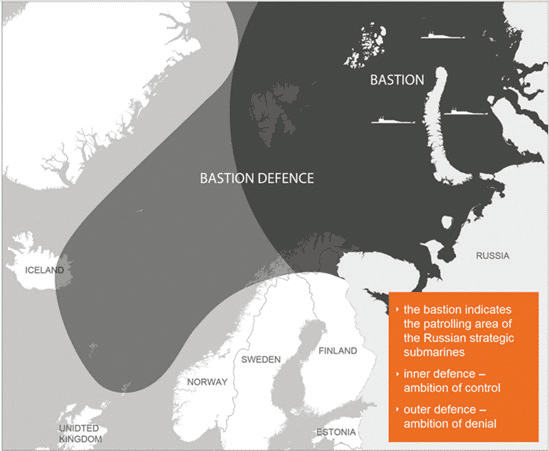

The need for greater NATO presence to balance Russian interests in the Arctic has become increasingly apparent since 2014. This is evident in their annexation of Crimea, attempts to limit freedom of navigation, and their breaches of other states’ sovereign airspace by military aircraft, coercive diplomacy against Sweden and Finland, and most importantly their unlawful invasion of Ukraine (Braw, 2022; Mackinnon, 2022). The Russian Arctic military infrastructure build-up, which has been going on for many years, has put them in a position where they could effectively enforce their territorial claims in the Arctic, such as their designation of the North Sea Route (NSR) as an ‘internal waterway’, (Danoy & Maddox, 2020: 76) which is blatantly contrary to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Furthermore, “Russian armed forces are assumed to have an ambition to control the Barents Sea and its surrounding areas” (Wegge, 2020: 363). They are now thought capable of directly assuming air, land and sea control of the dark grey areas shown on the map below as well as having anti-access and areal denial (A2/AD) capabilities in the light grey areas (Wegge, 2020: 363-364; Expert Commission, 2015: 21). Furthermore, in a potential conflict, Norwegian armed forces would be unable to defend its core areas if interest, as well as portions of its northern sovereign territory (Expert Commission, 2015: 15, 21).

Previous Initiatives

Until the annexation of Crimea, NATO was kept out of Arctic politics by the Arctic Council, in favour of inter-regional councils and diplomacy. The European Arctic states and Canada vetoed and discouraged all NATO initiatives involving the Arctic (Depledge, 2020: 81). Arctic security was thus driven by the Arctic Council, its security oriented derivatives, and the individual Arctic countries’ security policies. Because the shift away from this policy was so recent, the alliance “yet still has not agreed on an Arctic security policy” (Coffey & Kochis, 2021: 1). However, even without a coherent Arctic security policy, the individual Arctic NATO states, in particular the US and Norway, have had extensive military cooperation, which have increased since 2014.

Norway is the only country in the world with permanent military headquarters North of the Arctic circle. In 2020 the Norwegian government began the reopening of “Olavsvern bunker, a mountainside submarine base near Tromsø, closed in 2002, which has ‘9,800ft of deep-water underground docks that can house and refit nuclear submarines.’” (Coffey & Kochis, 2021: 2). In addition to this, Norway hosts US marines for Arctic training on rotational basis and have signed agreements for the US to build air and naval bases and military infrastructure above the Arctic Circle (Coffey & Kochis, 2021: 2). Most importantly, the “U.S. 2nd Fleet achieved full operational capability” in the end of 2019, it was reactivated in the face of Russian hostility after being disestablished in 2011 because of the seeming lack of threat from Russia (America’s Navy, 2019). The second fleet is responsible for the North Atlantic and will, according to its commander, Vice Admiral Andrew Lewis, have a special focus on the Arctic, “with the opening of waterways in the Arctic, this competitive space will only grow, and 2nd Fleet’s devotion to the development and employment of capable forces will ensure that our nation is both present and ready to fight in the region” (America’s Navy, 2019). Yet the fact remains, even in the face of the end of the policy of appeasing Moscow’s demands to keep NATO out of the Arctic, the alliance still lacks an Arctic strategy.

Recommendations

The first policy recommendation is to integrate the military cooperation in the Arctic regions between individual NATO countries to be under a single regional command structure. The Joint Warfare Centre (JWC) in Stavanger, Norway, main responsibilities are “education, training and exercises, and promoting interoperability throughout the Alliance” (NATO: 2018). The regional command centre should build on the institutional experiences and knowledge of the JWC Stavanger and focus on enhancing cooperation between “JFC Norfolk and NATO’s Allied Maritime Command (MARCOM)” and the United States 2nd Fleet (Masala, 2020: 5). It should also have the added responsibilities of coordinating all NATO efforts in the Arctic region. As mentioned, there is already extensive military cooperation between several individual NATO states in the Arctic and the proposed command centre would centralise and expedite the processes of such cooperation. A core part of this recommendation is “Establishing a third NATO Standing Naval Group (made up of NATO member states that have a particular interest in the Far North) for the region” (Masala, 2020: 5). These states would be the NATO Arctic states and the Arctic observer states in addition to possible enhanced military cooperation with Finland and Sweden.

The Second policy recommendation is the enhancement of NATO military cooperation with Finland and Sweden. While these two countries have historically been neutral, they have gradually shifted their position and are firmly within the political sphere of NATO and the West. The recent rising tensions with Russia saw Moscow attempt to intimidate Finland and Sweden. In a blatant attack on their sovereign right to choose diplomatic alignments the Russian Foreign Ministry recently said that Finnish and Swedish deepening ties NATO would face “serious military and political consequences” and “would require an adequate response on Russia’s part” (Braw, 2022; Mackinnon, 2022). Leaders of both countries responded by saying it is indeed up to them, and not Russia, whether they will join NATO or otherwise cooperate with the alliance. Whether or not they intend to join, NATO should strive to include the armed forces of both countries in its northern exercises. NATO should do this in order to unite behind the assertion that neither NATO, Sweden nor Finland will yield to Russian intimidation tactics. Both countries are strategically located and their inclusion in military cooperation would enhance NATO presence in the Arctic. Sweden is a major military force in the high north and it has recently boosted preparedness at the island of Gotland in the Baltic sea in answer to rising tensions with Russia (Försvarsmakten, 2022).

The third policy recommendation is for the NATO Madrid summit in 2022 in its new strategic initiative to agree on the establishment of a NATO Enhanced Forward Presence in the Arctic regions of Norway. This would be integrated with the abovementioned regional command structure and would add to this a standing battlegroup. One of the diplomatic demands Russia recently made in regards to the intimidation of Ukraine was pulling out battlegroups from the Baltics. By answering Russian coercive diplomacy by establishing a new enhanced forward presence battlegroup – this time in the Arctic – NATO would demonstrate determination and strength through not recognising Russian intimidation. In addition to this it would enhance Arctic military presence and serve as a serious strategic level deterrent against Russian ambitions and military planning in the Arctic (Rumer, et. al., 2021: 1; Wegge, 2020: 374).

Conclusion

As NATO is developing a new strategic concept in the run-up to the Madrid summit in June 2022, the alliance runs the risk of creating a strategy for the next decade that does not take the security challenges in the Arctic seriously. This essay offers three recommendations that should be taken into account in NATO’s current work on its new strategic concept: Firstly, it suggests creating a unified command structure for the region. Secondly, it suggests inviting Finland and Sweden to more integrated military cooperation with NATO. Thirdly, it proposes an enhanced forward presence battlegroup above the Arctic circle in Norway. With these recommendations in mind NATO have the chance take a decisive stance against Russian attempts at coercive diplomacy and outright military threat. NATO could enhance their Arctic security by many degrees by establishing a credible presence and deterrence in the Arctic. In the development of 2022 Strategic Concept NATO, by taking a decisive stance in responding to Russian hostility by increasing their military presence the Arctic region, will have the opportunity to add to the political pressure that is already being put on Russia.

Last ned pdf-versjon av notatet her:

Civita er en liberal tankesmie som gjennom sitt arbeid skal bidra til økt kunnskap og oppslutning om liberale verdier, institusjoner og løsninger, og fremme en samfunnsutvikling basert på respekt for individets frihet og personlige ansvar. Civita er uavhengig av politiske partier, interesseorganisasjoner og offentlige myndigheter. Den enkelte publikasjons forfatter(e) står for alle utredninger, konklusjoner og anbefalinger, og disse analysene deles ikke nødvendigvis av andre ansatte, ledelse, styre eller bidragsytere. Skulle feil eller mangler oppdages, ville vi sette stor pris på tilbakemelding, slik at vi kan rette opp eller justere.

Ta kontakt med forfatteren på [email protected].

Bibliography

- Parliamentary white papers

- Canada:

- Canadian Armed Forces, (2017) ‘Strong, Secure, Engaged, Canada’s Defence Policy’ Minister of National Defence.

- Finland:

- Working group of public officials responsible for Arctic issues, (2021) ‘Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy’, Finnish Government.

- Norway:

- Det Kongelige Utenriksdepartement (2020) Melding til Stortinget (2020-2021) ‘Mennesker, muligheter og norske interesser i nord’, Departementenes sikkerhets- og serviceorganisasjon

- Sweden:

- Regeringskansliet, (2020) ‘Sveriges strategi för den arktiska regionen’, Stockholm: Regeringskansliet.

- Canada:

- General Sources

- America’s Navy, (2019) ‘2nd Fleet Declares Full Operational Capability’, Americas Navy Press Office. Available at: https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/Press-Releases/display-pressreleases/Article/2237734/2nd-fleet-declares-full-operational-capability/

- Biden J. (2022) ‘Biden Holds Press Conference to Mark First Year as President | NBC News’, 19 January 2022 [Youtube]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RCp6kZL1BDg

- Braw, E. (2022) ‘Finland and Sweden Are Done With Deference to Russia’, Foreign Policy, 5 January 2022. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/05/finland-sweden-nato-russia-putin/

- Buchanan, E. & Strating, B. (2020) ‘Why the Arctic is Not the ‘Next’ South China Sea’. War on the Rocks (online), 5 November 2020. Available at: https://warontherocks.com/2020/11/why-the-arctic-is-not-the-next-south-china-sea/

- Coffey, L. & Kochis D. (2021) ‘NATO Summit 2021: The Arctic Can No Longer Be an Afterthought’, The Heritage Foundation.

- Danoy, J. & Maddox, M. (2020) ‘Set NATO’s sights on the High North’, Atlantic Council Scowcroft Centre for Strategy and Security, NATO 20/2020, pp. 75-79.

- Depledge, D. (2020) ‘NATO and the Arctic The Need for a New Approach’. The RUSI Journal, 165:5-6, pp. 80-90.

- Doshi, R., Dale-Huang, A. & Zhang G. (2021) ‘Northern expedition: China’s Arctic Activities and Ambitions’, Brookings Institute.

- Economist, ‘NATO is facing up to Russia in the Arctic Circle’, The Economist, 14 May 2020. Available at: https://www.economist.com/europe/2020/05/14/nato-is-facing-up-to-russia-in-the-arctic-circle

- Expert Commission on Norwegian Security and Defence Policy (2015) ‘Unified Effort’. Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Defence.

- Försvarsmakten, ‘Operativa beredskapsenheten sätts in på Gotland’, Försvarsmakten, 15 January 2022. Available at: https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/sv/aktuellt/2022/01/operativa-beredskapsenheten-satts-in-pa-gotland/

- Greenhaw, T., Magruder, D. L. Jr., McHaty, R. H., & Sinclair M. (2021) ‘US military options to enhance Arctic defense’, Brookings Institute.

- Ignatov, O (2021) ‘Behind the Frictions at the Belarus-Poland Border’, International Crisis Group.

- Keil, K. (2013) ‘The Arctic: A new region of conflict? The case of oil and gas’. Cooperation and Conflict 2014, 49:2, pp. 162-190.

- Mackinnon, A. (2022) ‘Swedish Foreign Minister: Joining NATO Is Up to Us’, Foreign Policy, 7 January 2022. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/07/swedish-foreign-minister-ann-linde-nato-finland-russia/

- Mackinnon, A., Detsch, J., & Gramer, R. (2022) ‘Russia Planning Provocation in Ukraine as Pretext for War’, Foreign Policy, 14 January 2022. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/14/russia-provocation-war-pretext-false-flag-ukraine-eastern-us-intelligence/

- Masala, C. (2020) ‘Maritime strategic thinking: The GIUK example’, Metis Institute for Strategy and Foresight.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization (2018) ‘The NATO Command Structure Factsheet’. Brussels: NATO Public Diplomacy Division (PDD) – Press & Media Section.

- Pincus, R. (2020) ‘Towards a New Arctic’, The RUSI Journal, 165:3, pp. 50-58.

- Skydsgaard, N. & Pamuk, H. (2021) ‘Blinken says Russia has advanced unlawful maritime claims in the Arctic By’, Reuters, 18 May 2021. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-has-advanced-unlawful-maritime-claims-arctic-blinken-2021-05-18/

- Villalobos, F. (2021) ‘As U.S. Shifts Arctic Strategy to Counter Russia, Allies Offer Valuable Info’, Rand Cooperation.

- Wegge, N. (2020) ‘Arctic Security Strategies and the North Atlantic States’, Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 11, pp. 360–382.

- World Economic Forum, ‘The final frontier: how Arctic ice melting is opening up trade opportunities’, The World Economic Forum, 13 February 2020. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/02/ice-melting-arctic-transport-route-industry/

- Zeman, J. (2021) ‘No Need to Read Between the Lines: How Clear Shits in Nordic Strategies Create Opportunities for the United States to Enhance Arctic Security’, RAND Cooperation